A bat dressed like a security guard stands in front of a mine opening closed off by a typical bat gate. A sign above reads “Bats only, no humans allowed.” Graphic by OSMRE Environmental Journalist Emily Isaac.

When you think of bats, you probably picture them hanging upside down in a cave, or as flying silhouettes against the full moon. You may not immediately think of abandoned mines, yet 29 out of 45 of America’s native bat species rely on abandoned mines for habitat. Abandoned and disused mines mimic the consistent temperature and humidity that many bat species need for their maternity roosts and hibernation. As much of their traditional habitat has been lost to human development and deforestation, these mines serve as a refuge.

But as bats flock to these mines, so can other unwelcome guests: namely, humans. The real spooky aspect of abandoned mines is not that they have ghosts, but rather the serious threats to health and human safety they contain. Many of these dangers, like unstable highwalls and shafts or lethal gases trapped inside, pose a serious risk to thrill-seekers who attempt to explore abandoned mines. As such, getting mine openings closed safely and quickly is a top priority for reclamation programs across the country.

How do you safely close mine openings and prevent people from entering, while still making sure bats have access? To address this problem, reclamation teams install specialized gates, a grid of metal bars with long horizontal slots that ensures bats and other small creatures can safely pass through. Installing bat gates is only one of many ways that OSMRE works to make sure bats are protected, during all stages of the mining and reclamation process. Compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act requires a holistic approach, which usually starts by identifying what endangered species reside in the project area. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maintains an online database that anyone can access to see which species live at a defined location.

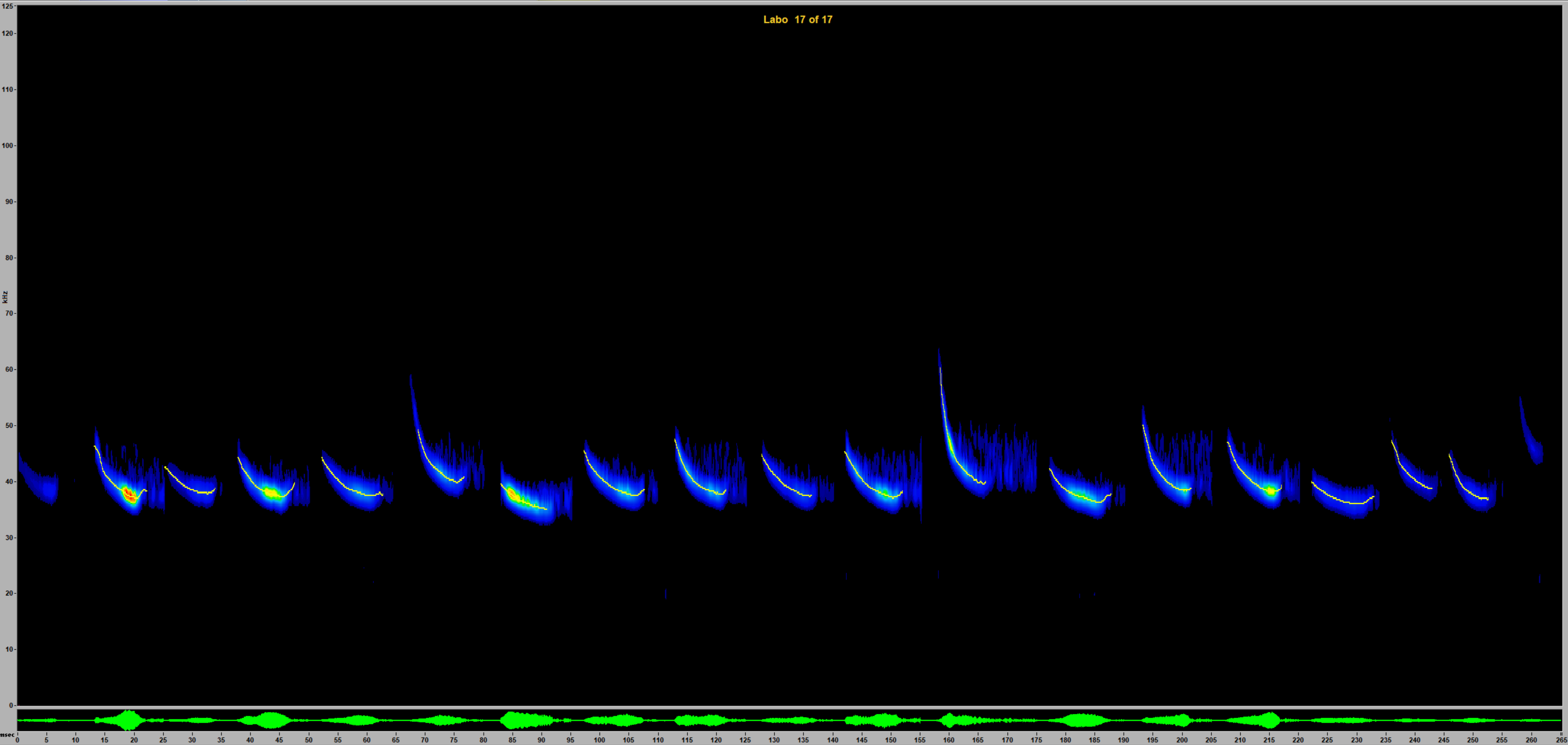

Another way to determine what species are in an area is through acoustic monitoring. Special recording equipment is deployed in the field and captures sound over several days—rather than having scientists stay up all night with a microphone! The recordings are then analyzed by a special software that amplifies and isolates animal calls. While staying on top of the latest surveying technology, OSMRE also brings experts together to share information and insight by organizing events like the bat talks at this year’s 2023 National Association of Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation Programs conference, which included presentations from Bat Conservation International and the USFWS.

A passive acoustic monitoring device on a previously mined land. The device was deployed to monitor bat activity at the pond. Courtesy of OSMRE ecologist Brian Dailey.

A sonogram and corresponding audio of an eastern red bat call, recorded in an open field in Ohio. Special software is used to enhance and separate out different sounds, which can then be turned into pictures. Courtesy of Brian Dailey.

If threatened or endangered species are present, mining companies or reclamation programs who wish to alter the area must prepare a protection and enhancement plan. These plans are tailored to the specific project site and include special considerations for each species’ unique needs. For instance, many bat species use caves and mines in the winter for hibernation, then migrate to tree habitat in the spring and summer. In this case, any work on a mine opening would be restricted to summertime while there are no bats present, and any tree clearing would be restricted to wintertime, while the bats are cozy inside their caves. Tree clearing usually takes place in a staggered manner, and previously forested areas must be returned to at least 70% tree cover afterwards.

Besides habitat loss, white nose syndrome has hit bat populations hard. White nose syndrome is a disease that affects hibernating bats, causing them to become more active than usual and burn stored fat they need to survive in the winter. The disease has caused an estimated 6.7 million bats to die since 2006. This means that more than ever, it is essential to make sure mining activities don’t cause undue stress to bats. According to the USGS, white nose syndrome is primarily spread from bat to bat, but humans can also carry the fungus on their clothing or gear. As a result, wayward explorers can spread white nose syndrome from one mine to another without realizing it, making timely and effective reclamation of mine openings even more pressing.

From the start of the mining process all the way through reclamation, OSMRE prioritizes the health and safety of bats and humans alike. It’s thanks to strong partnerships with state and Tribal programs, as well as other agencies, that our nocturnal friends can continue to soar through the skies.